Heathrow Airport’s cargo chief, Nick Platts, is experienced in rescuing “errant English-men” from his ten years as a Southern Ocean maritime patrol pilot in the Royal Australian Air Force.

Rather than chasing submarines or rescuing yachtsmen, Platts is now on a ten year mission to make Heathrow the “preferred transatlantic gateway” in Europe by 2020, and by 2025 “one of the best in Europe for a timely and predictable cargo process”.

It will not be easy, as Platts addresses the strategy and policy failings of past decades at the UK’s number one cargo hub, handling 1.5m tonnes in 2015.

“Heathrow has loads of transatlantic capacity, it is our biggest market and we have high frequency services to North America, but we are not the preferred airport due to the issues we have on the landside space, and a lot of people quote the horseshoe.”

The latter, named after its extended U-shape, was designed for smaller vans but now has to deal with heavy goods vehicles (HGVs).

“Between 30%-40% of our tonnage goes through the horseshoe at Heathrow. So it is not the biggest estate.

“We recognise that the forwarders and trucking companies do not like using Heathrow. The truckers send in an HGV to deliver 300kg and they are sat there for up to nine hours. That is an inefficient use of a resource.”

Platts came to Heathrow in 2012 as head of ground handling for airside operations, following a four year stint off-airport at nearby Poyle with parcel giant FedEx, setting depot strategy.

“At FedEx, my perception of Heathrow was that it connected us with the world and that we did not have enough capacity on a lot of lanes, so we were always fighting for more in the peak seasons.”

He “did not duck quickly enough” and became the chairman of Heathrow’s Association of Inter-national Courier & Express Services (AICES) during his last year at FedEx.

“I recognised by then that the industry was stuck in its ways and very slow to change. As an integrator I had absolute knowledge about a parcel in our network. I knew exactly where it was, when it was moving, where it was moving to and when it needed to be delivered.

“As soon as I handed that over to an airline at Heathrow, I lost it for a week and the only way I knew that it had arrived was when the FedEx receiving country scanned it into their facility.

“There was a big black hole and nobody seemed particularly worried about it.”

At FedEx, it was so very different: “We were engineering minutes out of our processes so that we could connect with flights. When I came to the airport, the forwarders and the handlers are talking about taking days out of the process. We are not even in the same ballpark as the integrators.”

Platts became “sick and tired” of FedEx colleagues moving to airport-based jobs and wanted to know why: “Are they paying more than us?”

A quick look at the airport jobs website revealed two positions that Platts could fill, and so he applied and secured his new role, but there was a tantalising hint of the future.

“My job description had one line that said ‘develop the Heathrow cargo strategy’. It was literally one line.

“I did not know any of the history. I started asking around, what have you done about cargo? It transpired that we had sold all the land off in 2010.”

Platts had two months to write a business investment case for Q6, the current control period for airport economic regulation administered by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

He resurrected an old project from 2009, to bring the cargo area inside the critical part of the airport, removing the control post, an idea shelved by the airlines.

“I managed to find it with six weeks to go. I dusted it off and put in for £16m to spend and that’s how we got cargo into the Q6 plan,” the first time cargo had been prioritised in 30 years of economic planning.

The strategy was picked up by Heathrow chief executive John Holland-Kaye and also became one of the five promises submitted to the Airports Commission looking into runway capacity for the south east of England.

When the commission’s final report came out, that cargo promise was the number two bullet point as to why Heathrow should get a third runway.

But Platts knows that he needs a data starting point, a benchmark, in order to measure progress.

And that is the problem.

“I don’t know because no one is prepared to share their data. I have been asking the industry for 12 months to give me hard facts and data on dwell and throughput times, and I don’t get it. One trucking company gave me some data but it took six months, even though they had telematics on board.”

He adds: “I have to go and ask the airlines for permission to use the airlines data, but the airlines don’t want to talk to me because they want me to talk to their handler.”

It would need only a small number of airlines inputting data to make a difference. Platts says that 13 carriers account for 80% of Heathrow’s cargo volumes, with three airlines being “quite strong”.

On the data and strategic planning front, Platts is looking to continental European airports, Amster-dam-Schiphol and Brussels, for inspiration.

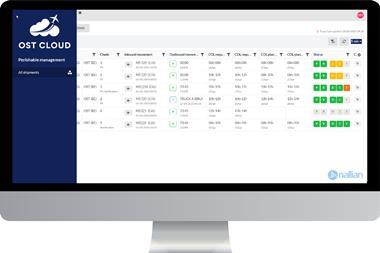

Heathrow is linking up with technology provider Nallian, which offers a cloud-based platform for BRUcargo to exchange business intelligence information securely between forwarders and handlers at Brussels.

“The Nallian tool is ready and we have got the IT set up on my side of the fence.

“All I need is for handlers and forwarders to start copying their messages and I can start get to get a better insight. I can understand what infrastructure and what processes we need to change.

“Equally, I would love the truckers to share with me regularly how many trucks they have coming into the horseshoe, how long they are spending in the horseshoe and how much time is idle.”

Heathrow has set up a cargo working group that is looking at several projects, such as a call-forward facility for trucks that will cut down on congestion and waiting times.

He points to ground handler dnata and its innovative processes and use of data at Heathrow.

Platts is also drawing inspiration from Enno Osinga, who led Schiphol’s cargo arm until his retirement last year.

Says Platts: “I had a few conversations with Enno.

“We spoke about how he took Schiphol from where it was to where it is today.

“It took him ten years and we agreed that there were a lot of parallels between the journey he has been on and the one that I am about to start.

“At Schiphol he had local councils that were anti cargo because of the noise and environmental issues, they did not see the benefits, and over ten years he has transformed it into what it is today.

“I have to be a realist because I don’t control any part of the cargo process at Heathrow. I am relying on third parties, so it is going to take time.”

As Heathrow awaits a government decision on a third runway for the UK hub, Platts says that his strategy is independent of that decision, but adds: “We have loads of capacity but some of the key routes are constrained. We can add 40 destinations and £211bn worth of trade to the UK [with a third runway]. For me to serve South America and the Far East better and to tap into the [Indian] sub-continent and Africa better, I need expansion and the extra destinations.”

He continues: “I will be competing against the Middle East three and Istanbul in the future, with new aircraft that can fly a long way with a lot of freight and people on board. That is a threat to the European market.

“Some 45% of my freight is transhipment, and it will grow to 55% in 15 years, so I need to be able to offer a slick efficient process that makes our belly capacity attractive to the forwarders to use us as a gateway.”

Platts’ no-nonsense approach has ruffled a few industry feathers. Will he achieve his goals?“Yes, because I am Australian and a stubborn bastard.”