Air cargo has been criticised in the past for being slow to digitalise its processes – but in recent years progress has accelerated.

Although the industry has been criticised previously for being slow to adopt technology and digitalisation, there have in fact been plenty of investments overthe past 40 years that demonstrate the industry’s progress.

The beginning of digitalisation in the industry was made possible by Microsoft, according to Christopher Hewlett, co-founder of BoxTop Technologies, a freight management software company.

“The big change 40 years ago was that PCs started to get affordable for smaller businesses,” he explains. But it was not an easy or rapid transition.

For many people, he says, “It was a frightening experience to buy, let alone maintain, the equipment. And then they were wary about clicking the wrong key and bringing the whole system down – and in those days, you probably could.”

Initially it was all about hardware. In the airfreight business, Hewlett says, it was Geoff Stow, founder of Redberry, who came up with pioneering software solutions so that smaller companies and freight forwarders could go down the digital path.

In the beginning, much of the software was used to recreate manual processes and often related to the accounting side of the business, rather than to the operations.

In the 1980s, computers were making an early impact on the air cargo industry, although there was some trepidation from users and the high cost of implementation meant they were limited to the larger players.

Some of the digital developments in the 1980s sound vaguely in line with what the industry is still aiming to achieve today.

For instance, one forwarder implemented anew system that could store customer details and shipment information, connect with accounting systems, produce documentation such as manifest and air waybills and even display rates by typing destination and type of cargo.

There were, of course, key differences: paperwork was still printed and users had to utilise a single computer terminal, rather than everyone having a shared network they could access from a computer on their desks.

Elsewhere, the 1980s even saw the start of cargo community systems. One such example was Schiphol Airport’s launch of Cargonaught in 1984.

The system aimed to move the industry towards paperless cargo by providing forwarders, airlines and handlers up-to-date information on freight consignments via screens on their own computers.

The end of the 1980s began to see desktop computers become increasingly commonplace in the office, but it was arguably the 1990s when they became standard and the internet and email allowed for greater connectivity with customers and suppliers.

The start of the internet age

The increasing use of computer technology and the World Wide Web in the 1990s combined to result in some key milestones.

Email sped up the rate at which air cargo stakeholders throughout the supply chain could exchange information. Elsewhere, IATA in 1996 lobbied global governments to sign the Montreal Protocol No 4 and end the use of paper air waybills to reduce costs and inefficiencies.

Another notable development was the first cargo capacity to become available on the Web in the form of the Cargo Online wholesale platform, also in 1996.

The digital platform connected forwarders and airlines by providing the direct marketing of cargo charter flights and an online searchable database of all available cargo capacity.

Despite increased internet use, there was, however, speculation over how quickly stakeholders would move from electronic brochure-style websites to more seasoned interactive offerings.

Many businesses focused their efforts on offering online track-and-trace shipment services.

Towards the end of the decade, companies made large investments to ensure their computer systems could withstand the impact of the so-called Millennium Bug – luckily the industry’s fears proved unfounded.

Paper age

The digitalisation of air cargo continued in the 2000s and 2010s with the industry increasingly recognising the benefits of digital technologies – such as greater efficiency, improved visibility, reduced paperwork, and enhanced customer experience.

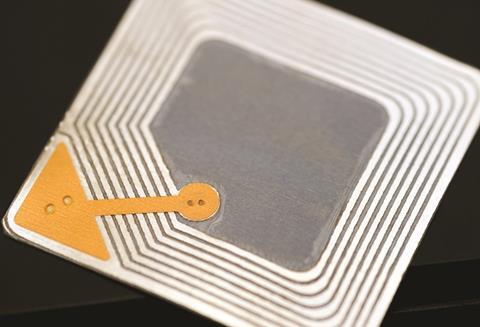

Also, cargo tracking improved with the use ofRFID and GPS, and cargo management systems continued to gain traction.

However, this period will probably be best remembered for air cargo’s slow progress in adopting digital technology compared with other industries.

While online sites such as Ebay and Amazon became standard ways of shopping and the passenger aviation industry moved to paperless ticketing and online selling, air cargo remained in the paper age, with airwaybills continuing to be printed and communication with customers and suppliers remaining stubbornly email and telephone-based.

Why the slow progress? The complexity and fragmentation of the industry, legacy systems, the regulatory environment, industry resistance and mindset and a lack of standardisation have all been to blame.

Arguably, the turning point for air cargo came in 2020 with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic. The constant rate and capacity fluctuations made digital data and connectivity key to making informed decisions.

Meanwhile, homeworking meant that digital communication became ever more important.

The biggest winners of this period were arguably the online booking portals that were able to provide real-time information and speedier booking than back-and-forth emails between various industry players.

Much of this was enabled by the rise of application programming interfaces (APIs), used for communication between different software applications for real-time data exchange.

During this period, the electronic air waybill finally gained traction and artificial intelligence and data analytics began to be used to analyse large volumes of data to help with optimisation and forecasting.

Despite the industry’s progress around digitalisation in recent years, most commentators agree that there is still a long way to go to roll out the digitalisation process and to reap the full benefits.

Tristan Koch, chief operating officer at software development company Awery, explains: “You might think that everything is digital to some extent already, but at the bottom end of the market people are still working on paper and spreadsheets. For smaller regional carriers, it’s paper and Excel.”

Even where there has been some degree of automation or digitalisation, it can be very difficult to persuade companies to take the next step.

“There are a whole lot of legacy systems – which were expensive. So, people are reluctant to give them up. But many are no longer fit for purpose.

“And where upgrades were done, this often involved adapting or adding to existing systems, so there is a lot of inherent complexity,” he explains.

One of the main problems is lack of cohesion. One solution has been to develop bridging software that allows different systems to communicate with each other.

Endless options

Koch says: “Now, we have APIs between different technologies. If relatively modern, the systems can be connected with bridging technology. But there is a limit to that.”

For many businesses starting on the digitalisation journey, the options seem endless and the problem is figuring out how to choose the best route.

Matthew Bradley, managing director, Community Network Services (CNS), has some advice: “Don’t try to eat the whole elephant; do it one slice at a time. The hardest thing can be taking the first step – so choose partners to work with and take it from there.”

Bradley was one of the speakers at the Digitalisation of International Trade and Transport seminar at Multimodal in the UK in June.

Samantha Brocklehurst, customer experience director – UK and Ireland, Maersk, added that the key “is getting people to be brave, to take a leap into the unknown. It takes role models – and then others will follow”.

Sam Blakeman, product marketing manager, Customs4Trade, says that the weakest link in the digital flow tends to be customs. His company is working to digitalise the customs process where there is still a lot of paper-based activity.

For Nallian, the provider of data sharing platforms and an ecosystem of collaborative solutions that power Brussels Airport’s BRUcloud, digitalisation is about producing a smooth, predictable supply chain. And that means collaboration between parties is key.

Joke Aerts, director of marketing, describes the process as “going from a linear, reactive supply chain to a connected, proactive supply chain. Information can cascade downstream... and allows you to register one version of the truth”. She says: “Our community system is complementary to customers’ own systems. We make it smooth and do not ask them to throw away all the IT they have invested in previously.”

Chief executive Jean Verheyen adds that the most value you can add for customers is where resources and/or space are in demand.

“Where the environment is challenging in terms of space – especially expensive airport space – being able to plan, or change plans as information flows through, is vital.”

Nallian asks potential customers to consider the cost if they don’t invest.

“Gains are at various levels – often the biggest point is what you could win if an operation runs more smoothly. With digital, everything is visible, which also helps resolve any potential disputes – for instance, about cargo loss or damage.”

The benefits of digitalisation have changed over the past 40 years. Initially, it was about saving time and reducing errors by not having to retype the same information over and over on different sheets of paper. Then it became about keeping up with the cargo – sending all the necessary information at the same time as – or even ahead of – the individual shipment.

As systems became more interactive and operated in real-time, exchanging data about predicted cargo volumes and forecasts – and, crucially, about delays and problems – allowed better planning of resources.

The watchwords became visibility and transparency and these are driving greater digitalisation.

Aerts says: “The expectation now is that you can trace anything you order personally – follow the driver to your door – so you must be able to do it in your own business. No one accepts that it cannot be done. The pressure comes from your customers.”

And that visibility is being used more and more by customers to check the things that matter to them, and to their own customers.

Bradley said that for CNS, digitalisation was about doing things with more visibility and transparency.

“But that purpose has undergone a dramatic change: customers and shareholders are asking ‘how do you play apart in sustainability?’ Digital is key to that. It optimises your supply chain. Digitalisation is our contribution to saving the planet – without sounding too dramatic.”

Collaboration aim

He added that companies have to be brave and embrace change.

“We also need regulatory change that requires us directly or indirectly to collaborate,” he said.

“It could be about CO2 emissions, where we need to exchange data through the supply chain. Or about provenance information, such as proving ethical labour standards.”

As a case in point, Lionel van der Walt, chief growth officer at Raft, an emissions data specialist, says forwarders need to take advantage of digital solutions as a matter of urgency ahead of new sustainability reporting regulations coming into effect across the US and the EU.

“The US climate regulations set to be published imminently, alongside those already in place in the EU, are predicted to have a major impact on the logistics industry, yetmost forwarders are either unaware, don’t understand, or are purposely ignoring these regulatory changes until they must comply,” he says.

“Time is running out for companies to adjust to the new era of collecting, managing, calculating and reporting the required environmental, social, and governance (ESG) data, including information on greenhouse gases. This can overwhelm most forwarders who lack the knowledge or resources to do so quickly and accurately.”

Brocklehurst says that trust is needed between disparate players.

“This has been a challenge and is likely to continue to be. If we plug quite sensitive data into one hub, how do we protect it? You can see why some are reluctant to come to the table and lean in and trust.”

Continued digitalisation seems inevitable, but Blakeman has a warning: “We need to be careful not to over-engineer things. It seems it can take 15 minutes to turn on a light in my house – as I need to download an app, and soon.

“Lots of solutions still rely on a ‘fall-back person’ somewhere. I don’t see AI filling that gap for everyone. Brokers and specialists are still involved. Don’t overlook people with their knowledge and experience.”